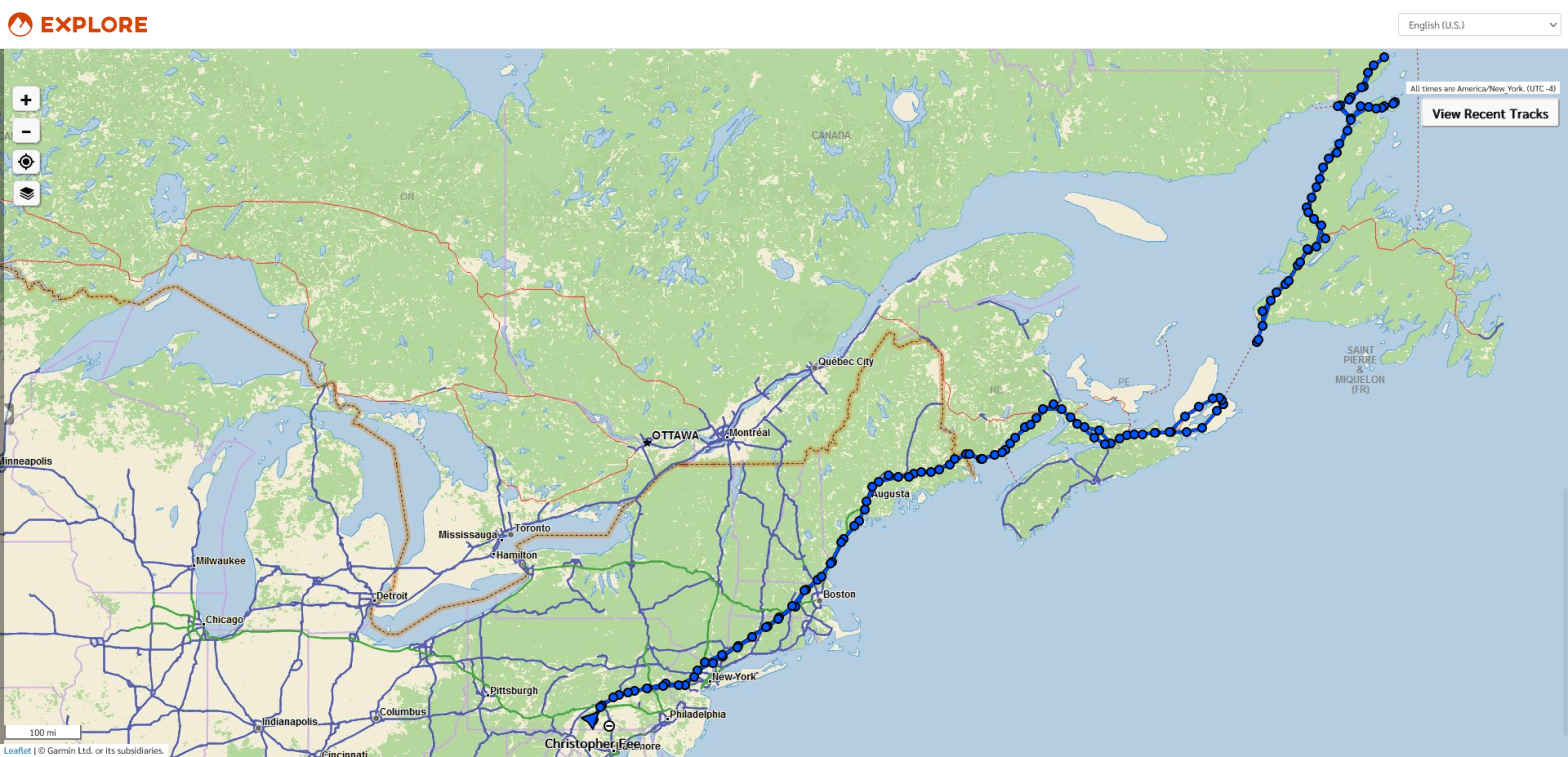

On July 7th, Team Viking is scheduled to set sail for adventure, careening up the Eastern Seaboard of the United States, hopefully crossing the Canadian border without mishap, and cruising across New Brunswick and Nova Scotia en route to our ferry departure from North Sydney, NS to Port aux Basques, Newfoundland, at noon on the 9th. We are scheduled to spend two days at Gros Morne National Park on our way to the ferry from St. Barbe, Newfoundland, to Blanc Sablon, Quebec. From there it is a short way to our base camp at Pinware River Provincial Park in Labrador. We plan to spend a week exploring the coast of Labrador and all the beauty and richness it offers before crossing back over to Newfoundland and spending a week navigating the coast of that island in the vicinity of the Norse settlement site at L’Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site. When internet access allows, we will attempt to add entries to this blog detailing our adventures. Throughout our trip, we will be tracked via satellite, and interested readers may follow our journey in real time, if you allow for short intervals as the electronic messenger ravens bounce around Valhalla and Jotunheim before returning to the mortal plane of Midgard. The map will update at 10-minute intervals, according to the will of the electro-Norns, although we will seldom journey at night. The map-sharing function for our peregrinations will begin at NOON on Thursday, 7 July 2022:

There & Back Again: A Viking Journey

To my mind, Team Viking’s expedition has been a tremendous success. We were able to trace relevant sections of the route the Norse likely took around the tip of Labrador into the Strait of Belle Isle and along the coast of Newfoundland. We paddled right up to the Settlement Site at L’Anse aux Meadows. We were able to examine this key location—and a number of other relevant physical places and imaginative spaces—both on land and from the water. We were able to note, up close and personal, the realities of wind, weather, tide, and currents that the Norse very likely encountered, at least during the summer sailing season throughout the relatively warm period in which the colony was founded. This, by and large, is what we had set out to do: To paddle, at least in brief and in part, In the Wake of the Vikings, and to see what insights our adventures might afford us into the experience of those earlier seafarers. Our blog entries provide some examples of some of the thoughts that were foremost in our minds during our adventures. As we reflect upon these words during our work on our book manuscript in the coming months, they will, as it were, provide plenty of grist for our intellectual Amloði’s mill (a bit of Old Norse Eddic humor for the Hamlet fans out there!)

It is important at this point, however, not to claim too much: First of all, we were not following some sort of Viking Age chart that showed us exactly where such-and-so Norse ship departed and arrived, with all the waypoints conveniently noted. No such chart exists, of course, and even if it did, we wouldn’t have been able to paddle from Greenland to Baffin Island to northern Labrador and down the long, long coast to the Strait of Belle Isle. We never could have accomplished that, even if we had the time. Our original plan, in fact, had been to spend the bulk of the summer, with most of the ice gone and the best paddling weather (from early July through mid-August) upon us, navigating a little ways down the eastern coast of Labrador and thence into the Strait of Belle Isle. We had hoped to have favorable conditions around the shortest crossing point (perhaps around Point Amour) and to paddle over to Green Island Cove (or whatever point the wind most easily allowed) on Newfoundland and thence up the coast to L’Anse aux Meadows. Although the crossing of the strait itself could have been accomplished in one very challenging day, the rest of the trip would have taken us 4-6 weeks, at best, even given excellent conditions, and of course one can’t count on that, as our own experience has illustrated amply.

With Russell’s death, however, we had to reimagine everything, and so we chose to focus on the most important pieces of the adventure we could still manage with just the two of us. We missed his friendship and his joie de vivre more than anything, but we also felt very keenly the absence of Russell’s deep and comprehensive knowledge of paddling in general and paddling Baffin and Labrador in particular. We subsequently were quite deliberate in using our paddling experiences to gain insight into the realities of navigating the particular coastlines on either side of the strait and in close proximity to L’Anse aux Meadows. What our book loses as an adventure narrative, therefore, we hope that it will gain as a focused examination of the realities of wind, wave, and water in the immediate vicinity of the Norse Settlement.

In addition, the meteorological, economic, political, and virological realities of our own point in time seem particularly instructive in a study of the Norse experience in North America. As the more diligent readers of our blog posts will know, we had to postpone this trip multiple times due to the pandemic. Now, a world epidemic didn’t end the colony at L’Anse aux Meadows, to be sure, and the research seems to indicate that it wasn’t the primary direct cause of the failure of the Greenland colonies, either. If we have learned anything at all in the past couple of years, however, it is how interconnected seemingly disparate things can be, and pandemics clearly have significant economic consequences. In our discussion of the Greenland colonies, we will note ways in which factors such as the collapse of the walrus ivory market and the economic aftermath of the Plague had an impact on those colonies. Climate change was also a factor, which is of course of immediate interest to us in this day and age. The fact that the Norse colony a L’Anse aux Meadows would have been founded during a period of significant warming was not lost on us, visiting Newfoundland during a summer of almost unprecedentedly high temperatures. Again, one does not have to claim that climate change is the most important factor in a given instance to note how it clearly may play a significant role. The issue of First Contact between Europeans and Indigenous Americans likewise was hard to ignore during our travels. Given that the Pope was in Canada when we were, apologizing for the treatment of Canadian First Nations, helped us to keep that aspect of the Norse saga accounts of the Vinland colonies in sharp focus.

In short, our voyage In the Wake of the Vikings was successful because we used the opportunity afforded by our adventure to think in disciplined and deliberate ways about how what was going on around us here and now could inform more fully our study of there and then. In a somewhat literal manner, this often meant paying close attention to the nuts-and-bolts of navigation, as well as to the ongoing challenges of wind and weather and land and sea. More metaphorically, however, we took the opportunity to draw parallels between our research into the people and places of what we have termed the “Norse America” of a thousand years ago with the realities of climate, economics, and intercultural conflict in contemporary Canada.

Thank you for being our shipmates on this journey!

Held og Lykke og Gode Rejser!

Our Garmin Mapshare function of the adventures of Team Viking is now deactivated; an image of the final map of our overall route is attached to this blog.

Vikings in the Mist: Peering through the Fog at Silhouettes of Labrador and Newfoundland

Fog is the atmospheric condition when the cooler temperatures and warmer environments collide to create particles of moisture. To me, nothing is more beautiful than to wake at first light on a mountain pass and to see fog in the valley and ravines below, with small peaks peering through and with the sun warming the summits. The scene is mystical, magical, and serene. In due time, as we know, the fog burns off as the atmosphere recalibrates and the moisture evaporates.

Though fog hampers our ability to see our surroundings, whether in the car on a highway, on a snow-packed mountain, or on the water, it does cause us to pay more attention to our inner self and our other senses. To this day, I have never seen the summit of Mt. Washington, though I have seen the silhouette of the observation tower and experienced the snow-swept parking lot. I have a limited understanding of what it is like to be in the middle of the Baltic Sea on an open water crossing; all I know is that I felt like I was a gerbil on a treadmill with fog horns from nearby ships blowing in front and then behind me. On the summit of Ben Nevis in Scotland, I still question if I were standing on the extensive cornice or not; I could not discern between the snow, the sky, and the void that was somewhere in the vicinity of where I was standing. I backtracked and retraced each step with care, somewhat akin to the kid in The Shining, when he was trying to hide his snow tracks from Jack while in the maze.

Though fog can cause moments of uncertainty, confusion, and doubt, it can also challenge us to see and to experience the world and our environment in a very different dimension. It forces us to stretch our vision in the hopes we can find shapes and outlines. We seek out shades of white and dark that help to provide clues of our actual location and the security of the environment’s handrails and footrails, which are the features to be found on a topo map and chart. The fog forces us to leverage sounds, smells, and instincts, pushes us to rely more intentionally on mathematical calculations (distance, time, speed, arc) to determine location, and taps into our creative space of wonder and curiosity.

Curiosity and wonder fascinate me the most while padding in the fog. While on the water off the coast of L’Anse aux Meadows, the fog, though not extremely dense, did create a white tapestry off in the distance with silhouettes of landmasses. It piqued my creative interest to wonder what it was like for the Norse to navigate across the Strait of Belle Isle from Labrador to Newfoundland and to establish a colony on the northern point. It could have been a crystal clear day when they first made landfall, though I can imagine metaphorically there was a great sense of fog around where they were and what was to come: wonder and curiosity.

Since returning from our sojourn to the north, I have been peppered with questions about Labrador and Newfoundland’s locations. What was the food like? The environment? The people? Now precisely WHERE is it again? These are the top four questions I have fielded since my return. Though the landmasses are just north/northeast of us and easily accessible, I feel humbled to have visited these vast spaces inhabited, hunted, fished, and sourced for thousands of years to sustain one culture after another culture. As the saying goes, you don’t know what you don’t know. I realize now that I lived in a fog for the few weeks Chris and I were visiting, exploring, and learning about the lands and waters of our northern neighbors. Other than knowing where Labrador and Newfoundland were via maps and charts, I now realize that my interactions with the people we met and befriended provided mere silhouettes of the much fuller realities of the cultures, lives, and pride of Labradoreans and Newfoundlanders. I had to draw on all my senses and past experiences to move into wonder and curiosity—and, as the fog started to lift slightly and to reveal its power just as I was leaving—I realized that I yearned to return to learn and to experience more.

I hope that my words will inspire others to do the same. It is more than worth the trip.

Our Garmin Mapshare function of the adventures of Team Viking is now deactivated; an image of the final map of our overall route will be attached to the final blog.

Homeward Bound: The Fast & Furious Return Voyage of Team Viking

I woke up Monday morning in Corner Brook, Newfoundland, just a little over two hours’ drive from Port aux Basques, where the Marine Atlantic ferry departs for North Sydney, Nova Scotia. The overnight ferry doesn’t leave until 11:45 PM and normally check-in is recommended two hours prior to sailing, but the scuttlebutt around the campfire at L’Anse aux Meadows had suggested that cars with trailers and RVs should be early, so I headed down after lunch. I was 9 full hours early, and I was third in line in the now familiar “goofy lane.” There were many trucks there already, as well, and by dinner-time the parking lanes were pretty full, so I was happy I had been cautious. Until a light drizzle began to fall later in the evening, there was something akin to a festival atmosphere in the lot, especially amongst the motorcycle fraternity. Boarding itself was fairly quick and uneventful, and once we were onboard, most of us in the reserved seating areas were fast asleep, albeit in a slumber interrupted and punctuated by the snoring, hacking, coughing, snorting, sneezing, and spitting all around me, always a bit disconcerting in these (hopefully!) nearly post-pandemic times. It should also be noted that, while Marine Atlantic offers top-notch service in many ways, the reserved seating recliners (while comfortably padded) are simply not built for those with more Jotun-like frames.

This may explain why I awoke about an hour before our scheduled arrival at 7:00 AM. That’s Atlantic Time, by the way, as we had gained back the half hour from Newfie Time during the crossing. I was one of the first off the boat, and as I pulled onto NS 105 West in the early morning mist, I realized that I’d gain another hour when I crossed into the US from New Brunswick. It seemed clear at that point that, kind Norns willin’ and traffic don’t snarl, I should be able to make it well into Maine before dark. This proved to be the case, and after a long but uneventful drive on another beautiful, windswept day—including a fast and friendly crossing at the border—right around dusk I pulled into our Maine base-camp, operated by Team Viking Official Pit Crew Nancy and Bucky Brown. Greeted by Bucky proffering a frosty libation and a steaming bowl of Nancy’s chili worthy of any Viking, I sat down to feast and to fill them in on our adventures. Soon thereafter, I turned in for my last night on the road, determined as I was to make it home before dark, now that the dragon’s share of the journey was behind me.

The final leg of the journey was likewise unremarkable, except for a couple of slight miscalculations that don’t seem to have added any real time to the trip. Just as the sun was setting, I pulled into my home port, nearly 1800 miles and some 84 hours after departing from L’Anse aux Meadows on my solo voyage home. After several weeks on the road, on the water, and in the field, the adventures of Team Viking had finally drawn to a close. Any trip home can seem anticlimactic, but it also may offer to the thoughtful traveler the leisure and the opportunity to process and to reflect upon adventures that may have unfolded in a rush. I certainly found this to be true for me, and in fact it was one of the only true benefits of making the homeward journey on my own. This being the case, .John and I both plan to write final blogs assessing our trip with the benefit of hindsight and considering which aspects we will examine in more detail in our book. Stay tuned for those!

We have plotted many of our adventures on this map:

Sketches of Vinland: Attempting to Catch Glimpses of Newfoundland through the Spy-Glass of History

As I drove back down the Viking Trail alone the Sunday after John’s departure, I enjoyed stunning vistas of the sea for long stretches. Once Route 430 shoots west over to Eddies Cove, it hugs the coast of the Strait of Belle Isle for more than 20 miles, all the way to Anchor Point. It then swings around St. Barbe Bay (and the ferry across the strait), continuing down the coast (now along the widening Gulf of St. Lawrence) for almost another 150 miles. Finally, it swings inland along the fjord-like reach of the East Arm (protected to some degree by Norris Point) as it hurtles through stunning landscapes and seascapes towards its terminus at Deer Lake. It was a glorious, blindingly bright morning, and as I drove along the water, I considered the fact that Norse expeditions west of L’Anse aux Meadows would likely follow this counterclockwise route around the Island. I imagined that they would far prefer the protected waterways of the Strait of Belle Isle and the Gulf of St. Lawrence to the much more treacherous route clockwise along a jagged rocky coast pummeled directly by the North Atlantic. The winds in Newfoundland can be severe in any season, and the prevailing ones are from the west and southwest, so the Norse would have had to take that into account, in either case. Certainly the sailing season would not have commenced until the pack ice was reasonably clear, which limits the navigable portion of the year considerably.

At the suggestion of my old college chum Adam, his lovely bride Tanya, and her sister Joanne, I was due to spend the night in Corner Brook, which would place me just a couple hours from the ferry terminal in Port aux Basques, where I was scheduled to depart late on Monday night. Tanya and Joanne are from Corner Brook, so they kindly offered a number of suggestions concerning how I might profitably spend my time in their hometown, and the one that seemed most aligned with my journey In the Wake of the Vikings was to visit the Captain James Cook Historic Site. A statue and interpretative plaques there commemorate the fact that, before his name became a byword for sailing around and charting vast portions of the globe, Cook was assigned to chart the coast of Newfoundland after the Treaty of Paris in 1763 acknowledged British claims to the Island. The vantage point of the site also gives stunning, nearly panoramic views over the Bay of Islands, the City of Corner Brook, and the surrounding mountains and countryside. It was a spectacular day to take a lovely walk to a beautiful vista, so many thanks to Joanne, Tanya, and Adam! Along the way, I reflected upon our own attempts to chart sections of the coast of Newfoundland. We had done a bit from the water, yes, but also on foot, in the car, and poring over the excellent (although at this point, time-consuming and somewhat challenging to obtain) Nautical Charts of the Canadian Hydrographic Service (CHS). I should let John tell that last story, but suffice it to say that—even attempting to secure charts weeks in advance—we had to make multiple orders, hedge some bets, and finally throw ourselves on the mercy of friendly folks in Labrador to have our charts shipped to us there in time.

I also read and re-read relevant passages of the sagas to look for clues for actual places on the map that we should attempt to visit and to paddle. Some were clearly too far afield for a journey of only a few weeks, but others are difficult to identify with any real accuracy, no matter how many tourist bureaus, local guides, and insistent self-proclaimed experts may assert forcefully to have identified them. Let’s be clear: West of Greenland, the only reliably identified Norse Settlement Site is that at L’Anse aux Meadows, although some recent finds on Baffin Island argue persuasively that the Norse used that landmass—long associated with the place called Helluland (“Rock-slab Land) in the sagas—as a stopover point. More than that we simply cannot assert with any real confidence, whatever we may choose to believe. It is vital to remember that reputable scholars of Old Norse literature, Medieval Scandinavia, and the Viking Age take the saga accounts in general with a large grain of arctic sea salt. The reasons for this skepticism should be readily apparent when one considers the more fantastical accounts of the Norse sagas, which are populated with “Wer-Bears and Zombies and Dragons, oh, MY!” When you fold into this Nordic witch’s brew the controversies around such suspiciously convenient artifacts as the (somehow, against all odds) still somewhat disputed Kensington Runestone in Minnesota and the now utterly discredited so-called “Vinland Map” at Yale, and it is clear that one attempts to follow In the Wake of the Vikings at considerable peril. The channel markers for the journey seem shifting, at best, and one must avoid the false beacons of latter-day historical wrackers in this attempt. The history of Newfoundland provides its own stark warnings in this regard, and, as Gollum might put it, it is vital when such will-o’-the wisps arise that we “don’t follow the lights.”

The sagas, in short, are clearly not “history” as we understand the term. Still, archaeological evidence does at times support some aspects of Medieval accounts, and we must take care not to throw the proverbial baby Viking out with the long-ship bilge-water. Thus, we need to keep both an open mind and a critical perspective. The excellent modern Nautical Charts, based in some measure upon the work originally produced by Captain Cook, offer in this regard a telling counterpoint to the vague but compelling tidbits we may draw forth from the sagas. It should set off alarm bells whenever these tidbits sometimes seem to fill in beautifully the gaps in the evidence that remain to us, a thousand years after the Norse reached L’Anse aux Meadows. We need to be careful, methodical, and rigorous in the assessment of our sources. The sagas sing us a siren’s song, encouraging us to set a course for adventure In the Wake of the Vikings. I for one am glad and grateful for that poetic impetus, but we must not allow beautiful dreams to cause us to ignore hard and fast realities. We must be cautious in our critical assessment of the relationship between literary license and verifiable fact. In sum, we must put our faith in more prosaic charts when we want to navigate safely through hidden shoals.

That was the lesson my visit to Captain Cook impressed upon me.

[https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/121019-viking-outpost-second-new-canada-science-sutherland]

[https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/did-viking-woman-named-gudrid-really-travel-north-america-1000-years-ago-180977126/]

[https://www.npr.org/2021/09/30/1042029881/the-vinland-map-thought-to-be-the-oldest-map-of-america-is-officially-a-fake]

[https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/30/us/yale-vinland-map-fake.html]

[https://www.minnpost.com/mnopedia/2020/05/the-kensington-runestone-minnesotas-most-brilliant-and-durable-hoax/]

[https://news.prairiepublic.org/main-street/2021-01-11/secrets-of-the-viking-stone-natural-north-dakota-nd-museum-of-arts-laurel-reuter]

[https://archive.macleans.ca/article/1973/1/1/the-wrackers-of-newfoundland]

[https://www.heritage.nf.ca/articles/environment/climate.php]

[https://www.charts.gc.ca/charts-cartes/index-eng.html]

Speaking of reputable maps, we have plotted many of our adventures on this one:

Farewell to John: Team Viking on the Cusp of the Long Road Home

When I dropped John off at the airport last Thursday, the paddling portion of our adventure was well and truly over. My skills are not advanced enough to solo the most interesting water in the immediate vicinity of L’Anse aux Meadows, and the more placid stretches would just frustrate me. It’s also hard to load and unload those big fiberglass beasts by oneself, without doing damage to the fragile shell (or my still more fragile back.) We therefore strapped and locked the boats on the racks in preparation for Sunday’s launch on the first leg of my 1800-mile, 35-hour drive (complete with overnight ferry.)

That’ll be the subject of a later post.

In any case, we spent Thursday morning and early afternoon pulling, cleaning, drying, organizing, and packing our gear. It was a task of some proportions in its own right. After we had finished and had something to eat, we left for the airport.

St. Anthony Airport is some 22 miles west northwest of St. Anthony, Newfoundland. It’s about twice that from L’Anse aux Meadows, and interestingly, from that site one doesn’t drive past the town of St. Anthony along the way: While the town is at the very end of Route 430, going to the airport from the Norse settlement requires one to backtrack back down the Viking Trail.

“Airport” may be a bit generous; “airfield” would probably be more accurate. I’ll let John describe his homeward-bound odyssey in his own post. Suffice it to say that, when we arrived, there were a handful of cars in the parking lot, and two more in a nearby and somewhat grassier lot marked “Long Term Parking.” We could see no planes at all, either on the ground or in the sky. We walked over to the door and put on our masks, as the sign bid us do, and then entered the facility itself, which is very nice and clean and modern, if quite a bit smaller than the larger ferry ports we’ve visited on this trip. There was one single soul that we could find in the public area, and he proved to be the lone grumpy and misanthropic person we’d met throughout our travels. I was under the impression that he was pretending we didn’t exist and/or attempting to will us to combust spontaneously, but I’ll let John describe that encounter. In any case, once a security guard wandered into the building, John and I said farewell, and I left to return to our camp, alone for the first time in our adventure.

To stave off any feelings of isolation as the last Viking left to represent the Team, upon my return to camp I was bound and determined to get right to work. I had decided to spend the couple of days I had left on site hiking around L’Anse aux Meadows and the nearby coastline, absorbing impressions of the place, and thinking and writing about those impressions. I also was in the process of soliciting some local advice concerning visits to potential spots of interest on the long road to Port aux Basques, where the ferry departs for Nova Scotia.

Right before I got back, however, about 800 yards from camp, I passed a young moose. From a distance, I had thought it was a runaway horse, as if that makes much sense. To be fair, I’ve had runaway horses in my front yard. I don’t have a lot of experience with moose.

In any case, it vanished almost as quickly as it had appeared.

I took this apparition as a good omen, and a totemic one, at that, because my brother and I often refer to each other as “Moose,” as that was what our dad used to call us.

I felt revitalized and ready to continue our epic quest to seek insight In the Wake of the Vikings.

More about my ongoing adventures later….

We have plotted many of our adventures on this map:

Visiting “VikingLand:” The Disneyfication of L’Anse aux Meadows

From the moment that one exits Route 1 at Deer Lake and begins the 526 KM (327 mile) journey along “The Viking Trail”—as Newfoundland Route 430 officially is known—which takes one to the turn-off for L’Anse aux Meadows and eventually ends at St. Anthony, one begins to see growing signs of Viking branding and marketing. These, of course, reach a fever pitch in the immediate vicinity of the Norse Settlement Site, but let’s get real: Hopeful entrepreneurs are hawking plastic horned helms at gas stations half the Island away, and the Island is BIG (nearly 43,000 square miles; a bit bigger than Tennessee, a bit smaller than Louisiana. It’s the 16th largest island in the world, and the roads are neither very good nor are they often direct. So Newfoundland, if anything, SEEMS even bigger than it is. And that’s not counting Labrador, which is much, MUCH bigger, and part of the same Province).

In any case, a few Vikingesque business ventures in the immediate vicinity of L’Anse aux Meadows are worth a visit, and I’d be lying if I claimed that a select few of some of even the very cheeziest didn’t seem kind of fun. We live just outside of Gettysburg, so we have been well aware of the sort of economic development spurred by what, for lack of a better term, one might term “marketable history nuggets” for quite a long time. Having lived in Scotland and Denmark and having spent a fair amount of time in Iceland and the Northern Isles of Britain, I’ve also experienced a wide range of specifically “Viking”-themed marketing in my time. These have run a very wide gamut from the tasteful gift shops of well-preserved and interpreted archaeological sites to thoughtful, privately-financed living history, to nightmare-inducing animatronics, to bog-standard fast-food and cheap trinkets with dragons, horned helmets, and/or longships crudely stamped on them.

Something interesting about the growth of the Viking-themed market on Newfoundland, however, is the fact that, until the 1960’s, there was no archaeological evidence whatsoever to support the saga references regarding the settlements that eventually were identified at L’Anse aux Meadows. It is certain, in any case, that there was absolutely no traditional island population with a folk knowledge of Norse ancestors, because to the very best of our knowledge, the Norse settlers on Newfoundland just packed up and left: They left no European descendants behind. Therefore, unlike the situation in Iceland or Scandinavia or even the Northern Isles of Scotland, the current residents of Newfoundland have no real connection to the Norse other than geographical proximity to a fairly small archaeological site and very vague cultural ties. In addition, this very sense of “cultural connection” can be highly problematic, as Annette Kolodny suggests in her 2012 book, In Search of First Contact. We will explore similar themes in our book.

In any case, that is all by way of cautionary caveat. In addition to nearly countless gift shops and restaurants along the Viking Trail, in terms of the actual enterprises worth investigating further, the Vikingly venture closest to the settlement itself that is probably worth a stop and certainly would please the kids is called “Norstead: A Viking Village and Port of Trade on L’Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland.” This takes sort of a “Colonial Williamsburg” approach to the Norse Settlement at L’Anse aux Meadows, and seems to be a real crowd-pleaser. It certainly has gotten a lot of attention and won some awards. It is of interest, therefore, both as an attempt at living history and as a market-driven manifestation of the immense popularity of all things Viking, and the good, the bad, and the ugly that may entail.

In the immediate neighborhood, there’s also the Viking Village B&B, as well as the Viking RV Park (although I could sense nothing really Norse at the latter, I do have an unsolicited testimonial: Stop there for a great home-cooked breakfast and locally sourced and homemade Pigeonberry Preserves, Scones, and Muffins! The Moose Burgers are also quite good.) The Norseman Restaurant overlooking the statue of Leif Eiríksson is actually very good by any standard. Although the attached gift shop is a little pricey, the Medievalist in our party was thrilled to see a JOTUN-sized stack of the most recent excellent Penguin edition of The Vinland Sagas parked right by the cash register for the more discerning and literate impulse-buyer.

Going a bit further afield, there is even a “Great Viking Feast” in a spectacular, cliff-side coastal location at the end of Fishing Point Road in St. Anthony, the biggest town in the area, about a 40-kilometer, 40-minute drive from L’Anse aux Meadows. Yep: It takes a good 40 minutes to cover those 25 miles, and look out both for giant potholes and giant trucks attempting to avoid same…. St. Anthony is also the home of the Viking Mall (where one may find everything a growing Viking needs, including grocery, bargain, & liquor stores), as well as to RagnaRöck Northern Brewing Co., which bills itself as “The Brewery at The End of the World!” The bar-hands further claim it to be the northernmost brewpub in continental North America, but that wasn’t an important enough factoid for us to bother to check. Playing off the Marvel Universe as well as their (relative) proximity to L’Anse aux Meadows, the claim to be at the end of the world also comes from the fact that The Viking Trail (NL Route 430) ends in St. Anthony. This reality, (as even a quick glance at a map will show you) is not just idle talk, given the general state of the roads in Newfoundland and their “can’t get THERE from HERE” structure. Add to that the fact that the region around St. Anthony is isolated by virtue of its location at the extreme furthest end of the Great Northern Peninsula of Newfoundland, and you might just buy that tagline by the time you arrive. You’ll certainly be ready for a beer. I recommend Syn’s Oat’h Stout Oatmeal Stout. John prefers the Freyja’s Feathered Cloak Session IPA. And as a closing note, the unique spelling of RagnaRöck is due to the fact that, long before Dwayne Johnson had descended from Valhalla to dwell amongst we lesser mere mortals in Midgard, Newfoundland has been known as “The Rock.”

Some of these places are worth a visit in their own right, but our own interest in them is in the blatant, not to mention seemingly profitable, commodification of the Norse Settlement Site, as well as how this trend exemplifies broader, and at times sinister, cultural trends. That will be a subject of some scrutiny in our book.

But for now, we raise our mead-horns to our readers with a mighty Skál!

More from our Files of the Viking Trail soon.

We have plotted many of our adventures on this map; as our dear friend & colleague Professor Myers has wryly noted, one MAY find a goodly number of brewpubs along our route:

https://share.garmin.com/IntheWakeoftheVikingsCFee

https://www.newfoundlandlabrador.com/trip-ideas/road-trips/western/viking-trail

Jens the Overlander: A Modern-Day Viking Voyage from Hamburg

Late one afternoon, after we had pulled out of the water at Pinware River Provincial Park on the South Coast of Labrador, I had an interesting exchange with a friendly traveler interested in our attempt to paddle In the Wake of the Vikings. You see, he was doing something similar himself, although in some ways our experiences could not have been more different.

His name was Jens, and he was from Germany. He was one of several people we encountered who were touring all through the most remote and inhospitable regions of Labrador, anywhere vaguely connected by anything remotely like a “road,” in large, almost armored-looking, all-terrain RVs.

We discussed the research agenda of Team Viking, and then something else that we had in common with him: Although his was a very heavy rig and ours was ultralight, we both carried with us everything we needed to survive and even to be comfortable off-grid. We both had our own water supplies, filters, power, and heat, and everything else we needed. In a weird sort of way, we were opposite sides of the same coin, and we both stood out in every park or campground we entered. People were always approaching both of us to discuss our rigs. He politely asked about our experiences and equipment, and I reciprocated.

“Tell me,” I said, as our conversation moved onwards, “what do you call that type of vehicle?”

“I don’t know, exactly,” he responded. “I suppose that some people call them, ‘Overlanders.’”

I had seen such rigs before, and had researched them a little, simply out of curiosity. Champagne tastes but a mead budget, you understand. I’d never spoken to an owner of one before, however.

On the basis of my casual knowledge, the rig Jens was driving looked like a Unimog to me. Built in collaboration with Bavarian Ziegler Adventure, Daimler Truck refers to these beasts, the Flagship Off-Road Luxury Survivalist Overlander RVs of the Mercedes-Benz line, as the “‘MOG HOME’ FOR MODERN ADVENTURERS.” The Unimog is a rugged truck chassis produced by Daimler, the parent company of Mercedes-Benz. The classic conversion into an RV was built on a foundation originally produced as a military ambulance all-terrain vehicle model suitable for the most primitive off-road conditions. Eye-balling his rig, I’d estimate that Jens was driving something vintage in the range of the classic 1985 version of the Unimog Camper. It’s a thing of beauty, in its way, sort of like a classic Land Rover on steroids. Used and in good condition, these run something along the lines of a cool quarter million. New conversions seem to run anywhere from several hundred thousand to a million. Dollars. American Dollars. Just to be sure that we’re all on the same page.

“I notice that it has German plates” I continued, “did you have it shipped here?”

“No, not exactly: I came with it. There’s a boat you can take. Sort of like the Roll-On, Roll-Off (RORO) ferries you take to and from Newfoundland, only bigger. We sailed from Hamburg to Halifax. You can sail to a few ports in the US, too. You could ship the vehicle, but you can also travel with it, and have a cabin on board for the journey. Takes a couple of weeks. Just like the Vikings, eh? I recommend it.”

All that brings me back to my original point about Jens and his journey, and how that relates to his joke of being like a later-day Viking. He had, after all, sailed out from Hamburg, at the very base of the Jutland peninsula, out the Elbe River to the North Sea, and thence across the Atlantic, landing at Halifax, Nova Scotia, which could well have been within the pale of the Norse conception of “Vinland.” From there, he climbed into his giant, seemingly impenetrable, vague military-looking vehicle and began to explore the coast of Newfoundland and Labrador, much as the Norse had. Hamburg historically was cheek-by-jowl with Denmark, until the Second Schleswig War in 1864, after which Denmark lost control of most of the southern portion of Jutland. Vikings even had raided the city in the ninth century, and it was also occupied briefly by Danes in the early thirteenth. In any case, the region around the Elbe traditionally was the northern continental European frontier with what we traditionally think of as the “Viking” or “Norse” world.

I was reflecting on all this even as we spoke. Rousing myself, however, I noted that it was past time to move on and to get dinner started. We laughed, shook hands, and parted ways.

I wish him well.

I must also acknowledge that, although I certainly don’t really want his vehicle, I very much envy Jens his journey across the ocean, which would have complemented our own very nicely.

We have plotted many of our adventures on this map:

https://share.garmin.com/IntheWakeoftheVikingsCFee

Please note, in particular, that the company emphasizes: “It is possible to sail with your vehicle from Europe to North America on the same RORO ship. The prices include full board.”

In the Shadow of Leif Eiríksson: “Luck,” Leadership, and Legacy in the Norse World

On the day that John and I paddled to L’Anse aux Meadows to view and to visit the Norse settlement site for the first time from the sea, we returned to pull out at a boat launch only a few yards from the feet of a statue of Leif Eiríksson. The son of Eirík the Red, Eiríksson is remembered to posterity as “Leif the Lucky.” Landing so close to him was auspicious for a number of reasons, and so after we had pulled off our dry-suits and loaded our gear and boats, we wandered over to have a little visit. Thereafter, I made it a practice to take daily walks down past the settlement site to take a few moments with Leif. I tried to spend as much time as possible wandering several miles a day afoot along the coast in the vicinity, getting a feel for the landscape just as I have for the seascape. I visited at various times of day and in several distinct types of weather, just to try to experience what this place might have been like when Leif and the others trod these paths. As I did so, my thoughts often turned to the saga accounts of Leif. Since he has long been thought to have led the first European settlers to this site, Leif casts quite a long shadow, and in our book, John and I use him as a case study regarding Norse notions of leadership.

A good place to begin to understand why Leif would be a good choice in this regard is with the origin of his nickname. We learn in Chapter 4 of Grænlendinga Saga that, having rescued 15 men shipwrecked upon a rock, Leifr Eiríksson, var síðan kallaður Leifur hinn heppni, “was thereafter called Leif the Lucky.” Although this by-name is widely known to us and may seem almost clichéd, it actually describes perhaps the most important feature and admired trait of leadership during the Viking Age and throughout the Norse period of expansion, exploration, and colonization. Luck, like boldness, navigational skills, seamanship, and generosity, was a fundamental attribute—and in a certain sense a prerequisite—of a successful leader in the Norse world, whether that be as a battle chief, as a goði or headman in a local or regional Icelandic assembly, as a merchant skipper, or as a leader on a Viking raid. Successful leadership throughout the Norse sphere of colonization during and after the Viking Age was measured by a number of factors. These included physical abilities, martial prowess, necessary knowledge, required skill sets, and technical experience, not to mention proven performance.

Perhaps the two most important factors, however, would have been reputation and luck, which we understand only in part if we take these modern English terms to be the precise equivalents of their Norse counterparts. Reputation in the ancient Germanic world (of which the Norse are the northernmost subset) in many ways comprised all of the aforementioned aspects of experience and proven performance. Added to these, however, are crucial intangibles that are harder to quantify, including honor and integrity and the general tenor of that person’s relationships and interactions with others that we might put down to the “vibe,” or overall demeanor, of a person. Likewise, “luck” in this context means much, much more than generally having the dice fall one’s way more often than not: People and objects and places might be thought to be imbued with good fortune in a way that had tangible and quantifiable results for and impacts upon those who came into their orbit. Moreover, as you can judge for yourself if you choose to read our book, we mount what we believe to be a persuasive argument that there are clear parallels between Norse and modern notions of luck and its relationship to success, and that this has an impact upon how we perceive and quantify leadership abilities. This is certainly the case in expeditionary endeavors such as sea-kayaking and mountaineering. One of the points we raise is that adventure-based activities both test and develop not just the technical skills and leadership abilities of the individuals involved, but also the aura of experience, competency, and—yes—luck associated with them. This is another reason we have chosen to travel In the Wake of the Vikings as we have: the daily thrills, terrors, challenges, and opportunities we have faced, the excitement, the boredom, the unusual, and the mundane, all of these are part and parcel of both sea-faring and surviving in this region of the world. Tasting a little of it may give us some small insight—however slight—into some of the quotidian realities of the Norse facing similar elemental realities. In any case, they certainly give us ample discernment concerning our own abilities, qualities, and limitations, which is extremely useful in defining and understanding intangible aspects like “luck” and “leadership.”

We have plotted many of our adventures on this map:

First in Class on the St. Barbe Ferry

As we’ve noted in earlier blogs, our rig has gotten a lot of attention on campgrounds, in ferry lines, at gas stations, etc. The comments vary depending on the configuration of our equipment and the interest of our interlocutors, but it certainly seems eye-catching, gets us a lot of attention, and makes us new friends. The most interesting example of this phenomenon to date, however, was undoubtedly on our ferry from Blanc Sablon, Quebec, to St. Barbe, Newfoundland. As loyal readers may recall, we regularly are relegated to what one salty old veteran of the ferry system has dubbed “the Goofy Lane,” because of our unusual set-up and irregular length. When the Norns threw the ol’ Rune Sticks on a recent crossing, however, that played to our advantage. The ferry folks didn’t know quite what to do with ol’ Team Viking, and so after nearly everyone else was loaded, they ran us right up a center lane they had kept clear to fill in last, and awarded us with the coveted “First in Class” position, meaning we were both one of the last on BUT the very first off the boat. This was great for us for obvious logistical reasons, of course, but beyond that, it had the added bonus of making our rig the showpiece of the entire voyage. People wandered out onto the foredeck, saw our rig, studied it for a while, and then came back inside to tell their companions vocally and voluminously about it. Ferry voyages being what they often are, even on fair days, anything new and different gets attention. All that was somewhat gratifying, but what was really notable was the reaction of the crew, several of whom came out to look at it up close and personal. They studied and commented upon every aspect, from the fact that a Subaru Forester could haul it all to the design of the SylvanSport Camper to the colorful Point 65 North sea-kayaks to the RoadShower at the rear of the rig. And these guys gave us the impression that they had pretty much seen it ALL. N.B. to the cynical product-placement types out there, no, NONE of these companies sponsored this trip in any way. We just love our kit, and it’s only fair to note how much attention it all regularly garners, even amongst taciturn old salts on hauling ferries full of trailers on a daily basis…. That is all. More anon.

Follow along on our ongoing adventures in ten-minute intervals via this map:

https://share.garmin.com/IntheWakeoftheVikingsCFee

Keep up to date with our adventures and follow our movements through our blog:

In the Shadows of the Vikings: The Storm Clouds Gathered over the Living History at L’Anse aux Meadows

Having acknowledged in a previous blog the many positive impressions I have of the Parks Canada interpretation of the Norse Site at L’Anse aux Meadows, I do have some thoughts regarding significant short-comings in the interpretation of certain key aspects of the Norse experience in this settlement.

The “Meeting of Two Worlds” theme, in particular, explored in both the interpretive video in the Visitor Centre and the on-site tour of that name seemed to me well-meaning and engaging, but a bit too sanitized, perhaps purposefully naïve, and even bordering on the saccharine. Beginning with the theme that all humans began in Africa and then spread across the globe, the core notion was that the circle closed when the Norse and Indigenous Peoples stumbled upon one another. Although the video certainly notes that the relationships between the Norse and the Indigenous Peoples sometimes were less than harmonious, the overall tenor seemed to be a sort of cultural “Kumbaya Moment” of the common humanity and kinship of all peoples, highlighted by this historic meeting. That’s all well and good in its way, of course, and I personally am dedicated to acknowledging and embracing our common humanity. There needs to be accountability, however. This might not be the place to handle ALL of the history involved, but once the notion of First Contact is mentioned, there is no intellectually honest and truly just way to ignore the seamy underside that comes hand-in-glove with it. This is not least because of the ways that Indigenous Peoples historically have been and continued to be oppressed and marginalized (and “marginalized” is the most polite and antiseptic possible term I could use) in harsh and obvious ways. Given this context, it seemed a bit convenient and maybe even self-serving that the “Meeting of Two Worlds” approach even seems to skate lightly over the saga references that describe explicitly some of the more violent interactions between the groups. I’m thinking in particular of the sequences in Chapters 5 & 7 of The Saga of the Greenlanders and Chapters 10, 11, & 12 of The Saga of Eirik the Red. Now it is crucial not to rely on the sagas as gospel, but they do give general impressions of what later generations thought was most important about their traditional memory of their ancestors. It bears emphasizing that the representation of the Indigenous Peoples in those saga references ranges from the clearly unflattering to the cartoonishly offensive to the overtly monstrous, which is perhaps not surprising. What is perhaps a bit more surprising, however, is that the Norse in these sequences don’t necessarily come across as particularly noble or positive either. This is part of my point: The tensions, misunderstandings, misrepresentations, and injustices at the heart of these episodes were amplified immeasurably during the later periods of European activity in North America, and have continued right up to the present day. This is part of what we want to explore in our book. I’m not suggesting that these issues need to be foregrounded in every aspect of the interpretation of the Norse settlement site at L’Anse aux Meadows, but it certainly should be at the very heart of any “Meeting of Two Worlds” approach, especially in the present context of continued marginalization (literal and metaphorical) of Indigenous Peoples throughout the Western Hemisphere.

I should note that both John and I have ample personal experience with living history and with the public interpretation of history at a site with significant cultural weight. We’ve both lived and worked in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania for decades, John has led teams of guides and facilitators who engage the Battle of Gettysburg as an opportunity for personal, professional growth, and I’ve used the battlefield as a backdrop for probing conversations with my classes for decades. We’ve also both worked closely with personal friends and professional colleagues in this regard, notable Pete Carmichael, Robert C. Fluhrer Professor of Civil War Studies & Director of Civil War Institute at Gettysburg College, and Ian Isherwood, Associate Professor of War and Memory Studies at Gettysburg College and Harold K. Johnson Chair of Military History at the U.S. Army War College. I’m an American who has written about the hazards of romanticizing and whitewashing the history of the Battle of Gettysburg and the monuments that now populate its landscape, and who lives not far from the site of the infamous Carlisle Indian School. Frankly, coming from the States, I expected to hear a more nuanced Canadian response to the obvious teachable moment provided by the “first contact” between the Norse and Indigenous Peoples in North America. This was especially glaring during our visit, given that the Pope was scheduled to travel through Canadian First Nations the very next week to apologize and to offer healing for the horrible abuses wrought by the Roman Catholic Church in the Residential Schools. In this context, the “Meeting of Two Worlds” approach at L’Anse aux Meadows seemed like a missed opportunity, to put it as mildly as I might, given my stated affection for the site and its staff.

Follow along on our ongoing adventures on this map:

https://share.garmin.com/IntheWakeoftheVikingsCFee

Keep up to date with our adventures and follow our movements through our blog:

https://www.pc.gc.ca/en/lhn-nhs/nl/meadows

https://www.pc.gc.ca/en/lhn-nhs/nl/meadows/activ/decouverte-tours